One great thing about the university I work at, which we don’t shout about enough, is the fact that our library holds the massive IBA archive. What was the IBA? The Independent Broadcasting Authority was the regulatory body in the UK for commercial television (ITV & Channel 4) and for commercial radio - the precursor of Ofcom. It was founded in 1955, when it was known as the Independent Television Authority (ITV) before being renamed the IBA in 1973 with the launch of Independent Local Radio - strange really, that the UK had commercial television before it had commercial radio! The IBA archive is a paper (document) archive covering the years 1955-1990 and consisting of over 20,000 files and nearly 2 million separate documents. That’s a lot of documents. I could spend the whole of the rest of my career looking at the files and I would only process a fraction.

Some of the most interesting files in the IBA archive at those where you find specific examples of regulation and censorship that can shape broadcast output, with the IBA carefully monitoring as much as it could of the unceasing flow of diverse broadcast content from an unwieldy and tangled network of local and regional TV companies and radio stations, and responding to a similarly unceasing flow of complaints from the public. One of the recurring problems faced by the IBA was the question of material deemed offensive, whether this meant sex and violence in feature films broadcast on television, or swearing and vulgarity in comedy programmes.

When I worked at the University of Portsmouth on the Channel 4 and British Film Culture project, I began researching IBA files relating to the broadcasting of films on television. Channel 4 had a very broad, inclusive, open-minded approach to film programming, embracing everything from WW2 classics to world cinema, experimental film and animation. C4 were known for pushing the boundaries in terms of what could be shown on television, and gave the first television screenings of controversial work by pioneering directors like Jean-Luc Godard and Derek Jarman. I hope to write further posts relating to the Godard and Jarman seasons on C4 in the 1980s.

In doing this research I became interested more broadly in the character and remit of Channel 4, and the challenges this remit threw up for the IBA, who had to abide strictly by the Broadcasting Act of 1981. I eventually wrote an article on Channel 4’s remit and how this has influenced its programming for Learning on Screen’s publication Viewfinder, to coincide with C4’s 40th anniversary. Channel 4 was launched in November 1982 to entertain, educate and experiment (in the form and content of programmes), and to appeal to tastes and interests not catered for by ITV - these were the principles enshrined in its remit.

This remit to experiment and innovate meant that the Channel frequently tested the boundaries of the Broadcasting Act (1981), particularly Section 4 (1a):

4 — (1) "It shall be the duty of the Authority to satisfy themselves that, so far as possible, the programmes broadcast by the Authority comply with the following requirements, that is to say —

(a) That nothing is included in the programmes which offends against good taste or decency or is likely to encourage or incite to crime or to lead to disorder or to be offensive to public feeling".

The origins of the clause can actually be found in a clause devised by the Home Office in 1916, but never implemented, as the basis for official censorship of the cinema. The 1916 clause began 'No film shall be shown which is likely to be injurious to morality, or to encourage or incite to crime...' By 1954, the approach adopted by Parliament was more secular. Gone was the reference to morality and in its place came the concept of the greatest good of the greatest number; 'taste and decency' and 'not offensive to public feeling'.1

More broadly, contemporary arguments about taste and decency in the media have precedents in the arguments about the theatre in the 16th Century, the novel in the 19th Century, and the cinema, radio, and popular press, particularly during the inter-war years of the 20th Century. Drama and storytelling of all kinds have always involved the basic human experiences of love and death, neither far removed from violence and sex — take 'Tess of the D'Urbervilles' by Thomas Hardy, for example. The pervasiveness of television has intensified the disputes. Neither the theatre, nor the cinema in its heyday, reached the population as a whole with any regularity. With television, however, the conventions of the music-hall and the dramatic stage, as well as of the cinema, came within reach of everyone and those conventions proved unacceptable to some people and difficult to accept for others.

Television has, at least until the fracturing of group viewing patterns in the 21st Century, often been watched by two or three generations together, each with their own view of what is acceptable and what is rude or beyond the pale. This is, of course, at the root of much of the humour of Channel 4’s own Gogglebox!

Because of the flow of television, there has often been concern not so much about individual programmes, but about the possible effects of watching an accumulation of programmes over time. Of course the generational cleavages have been built in the television schedule, with its famous ‘watershed’ (the time of day after which programming with content deemed suitable only for mature or adult audiences is permitted).

What has often struck me when researching the IBA archive is that, whilst the IBA executives - naturally, as well-educated mandarins! - have a highly refined sense of this historical continuity regarding issues of taste and decency, this sometimes means that they ignore the central role of TV in society. Thus television comedy was often treated merely as the conventions of the music-hall and the dramatic stage brought into people's living rooms via the medium of television. This became something of a reflex - thus the IBA defended itself against Mary Whitehouse's criticism of Benny Hill by pleading the tradition of British music hall and end-of-the-pier shows (whilst having to conceded that living rooms were not, in fact, music halls or situated at the end of piers)!2

In this clip of Benny Hill’s Crook Report sketch (Hill’s spoof of the investigator Roger Cook), Ronald Crook briefly checks that he isn’t being recorded when divulging his unethical methods, as he doesn’t want to be overheard by ‘the plonkers at the IBA’.

This historical view can be useful but it tends to conceal both the role and responsibilities of the regulator itself, and the programme genres that television has developed for itself. What is the media regulator’s role in challenging offensive stereotyping and degrading depictions? What about violence in TV news reports about Northern Ireland or Vietnam in the '60s or '70s? What about the controversies thrown up by satirical programmes, TV soaps, or TV plays that have explored taboos and social questions? Can we use the generation of ‘offence’ as a gauge of permissiveness or the decline of deference?

Turning to Stuart Hood, who was both a high-ranking BBC executive and a pioneer of media studies, "what may be expressed on the screen is determined by the concept of 'the politics of the consensus' — the mainstream of political thinking within our bourgeois democracy". Consensus politics covers what the television authorities would define as the centre of the political spectrum — a band of opinion which may, from time to time, shift slightly to left or right, and which may expand or contract according to the political climate at any time. Thus, in the period covering the end of the '50s and the beginning of the '60s there was a noticeable relaxation of restrictions on what could be shown on BBC television.

This was the period of the so-called ‘Satire Boom’, which included BBC television programmes (e.g. That Was The Week That Was or TW3) in which some of the sacred cows of the establishment - the monarchy, the church, leading politicians, and other previously taboo targets - were mercilessly lampooned. At the time the BBC was blossoming under the liberal stewardship of Hugh Carleton Greene. The commercial companies were noticeably timorous during this period, and made no attempt to cash in on the manifest success of satirical programmes - in fact, they took refuge behind the Television Act and its references to good taste and decency.

That a sharply satirical programme like TW3 was ever put on can perhaps only be explained in the light of the political and economic conditions of the time. The Conservative government and the economy was buoyant; the boom meant that the sales of television sets were rising sharply, which in turn meant that the number of TV licences — and therefore the size of the BBC's annual income — was increasing steadily. Because of its sound financial position, which had every sign of continuing for some years, the BBC did not have to face the need to approach government to ask for an increase in the licence fee.

What caused people to take offence?

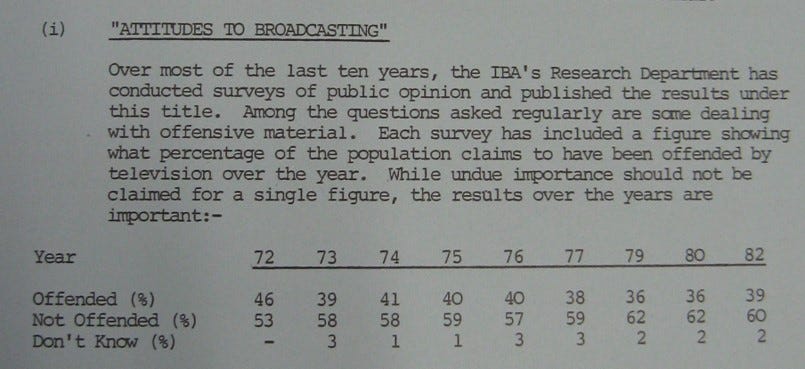

What caused people to take offence at television content? The 1970s (‘the decade that taste forgot’) provides a useful time period to study, not least because TV was pushing the envelope (some would say plumbing the depths) in terms of what was permissible in terms of language, social attitudes, sex and violence. An opinion poll conducted in 1973 found 20 per cent of respondents in favour of a total ban on nudity, sex scenes, swearing and blasphemy in television programmes, while only 14 per cent wanted scenes of violence between adults banned. Later, sex dropped to third place in perceived offensiveness, but bad language stayed well in the lead.3 The number of offended viewers picked up in the IBA's regular survey dropped off after the mid-1970s, after a high point in 1972.

But in June 1979 members were once more expressing concern about a decline of standards of taste in family viewing time, and at the beginning of the 1980s, while complaints were generally fewer, those categorised as ‘taste and decency’ were rising again. At this time IBA research sought to differentiate between the three factors usually named by that minority of viewers who claim to be offended by television. A report concluded:

There is no absolutely consistent pattern, but it seems fairly clear that bad language and overt sexuality usually cause more offence than violence, though 1981 figures (published in 1982) do show some rise in concern about violence. In term of the act’s phrase "Offensive to public feeling" bad language is, on this evidence, the largest problem faced by the IBA; and violence the least.4

It is interesting to compare this with more recent research. Ofcom’s Media Nations 2018 report (as summarised in the Radio Times) found that 42% of the British public cite bad language as the thing that most offends them on the telly. Just 38% of respondents said they were offended by sex on screen, with 37% put off by discrimination and 33% by depictions of violence. So this has remained remarkably consistent over the year. What is very different, however, is the number of people who claim to have seen something “offensive” on television in the past 12 months - just 19% of all adults, roughly half of the figure from 40 years ago.

Ofcom research from 2023 found that, whilst respondents feel that the level of sex and violence on TV has increased and intensified, with more graphic and realistic portrayals, people tend to underline the positive role played by TV in countering the potential negative impact of such content. This is a distinct difference from the 1970s, in that nowadays there is a much greater refusal to accept things like gender stereotyping, objectification, uncritical depictions of exploitative sexual relationships and so on.

How did the IBA monitor output?

The main thing people complained about in the 1970s was actually scheduling — e.g. when their favourite programme was shifted around in the schedule! This is something that has completely changed over the years — with non-linear TV, streaming services, and so on. People have far less cause for complaint on this count, as it is far easier to to ‘catch-up’ with something you have missed.

The IBA monitored and shaped broadcast output chiefly in two ways:

Quantity — from time to time ITV companies were asked to redraw their individual schedules to make sure that 'action-adventure' programmes were spread out more evenly or reduced in number

Content — Companies were required to submit in advance of proposed transmission a synopsis. This was circulated to particular members of staff. Any flagged issues would be raised with the Head of Department of the company. For 'acquired' (i.e. bought in) material a senior member of staff was responsible for viewing each film or episode, and would order whatever were cuts deemed necessary and recommend an appropriate time-slot.

To take bad language as an example, Stephen Murphy of the IBA (formerly a film censor at the British Board of Film Classification) astutely recognized that "there is no logical basis for concern about bad language, yet it is bad language which is the greatest source of offence in our programmes."5 This was the IBA's greatest problem under Section 4 (1) (a). The IBA also did attempt to defend control of bad language on TV with the argument that "one of the weapons of the dramatist has always been his ability to shock and offend. If bad language proliferates through every programme then the dramatist has lost an important weapon, and it will become necessary to create some new language of offence".6 Though bad language has long been regarded as a social problem, it is only since the 1960s that it has been at all widely used in television. The two World Wars, with an increasing participation by women in those wars, led to the first breaking down of social barriers. Theatre moved from its classical preoccupation with the politics and tragedies of the Court through the middle class traumas of Ibsen, Shaw and Galsworthy to the working-class, "kitchen-sink" drama of the British New Wave. In the North of England a group of novelists (Sillitoe, Barstow, Chaplin, Storey, the early John Braine) emerged with a much more gritty approach to dialogue. With the decline of British New Wave, and with the emergence of more social conscious writers and producers in British television, bad language found its way onto the screen. IBA had to strike a balance between the protection of freedom of expression versus the gratuitous use of bad language.

In the next part of this study of TV and ‘taste and decency’ I’ll look at comedy and light entertainment in the 1970s and will end with considering some of the radical changes brought by the multi-channel, multi-platform era.

Much of this background to the clause can be found in the IBA Paper ‘Taste and Decency’, 16th July 1982. ‘Contrary to Good Taste and Decency’ Vol. 30. IBA Archive. Box number 3996316.

Jeremy Potter, Independent Television in Britain Volume 4: Companies and Programmes, 1968–80 (Palgrave, 1990), p. 146

Potter, p. 144.

IBA Paper ‘Taste and Decency’, 16th July 1982.

Stephen Murphy, ‘Comedy and Light Entertainment’, 18th January 1982. ‘Contrary to Good Taste and Decency’ Vol. 30. IBA Archive. Box number 3996316.

Ibid.

This is a great intro. Looking forward to it continuing, maybe with some case studies of particular programmes?

Do you think the 1968 Theatres Act had a discernible effect on TV content or attitudes to it, or was that just a part of the general liberalisation that both theatre and TV were already embarked upon?