In September 2010, The Times ran a major supplement feature - titled ‘scooting back into style’ - on the style of the Mods, building on the success of the cyclist Bradley Wiggins (‘Wiggo the Mod’). The article suggested that this latest resurgence was partly the result of later Mods ‘growing nostalgic’ and passing their ‘passion … to their children’. This emphasises the significance of nostalgia and popular cultural recycling.

But the interesting thing is that youth cultures have not only always been prone to perpetual revivals, but have also quite consistently had ‘retro’ elements. We can see this in the unique fashion style of the Teddy Boys in the 1950s – the appropriation of Edwardian jackets and Western-style waistcoats and bootlace ties.

As much as they presented themselves as authentic, new and untainted by commercial manipulation, subcultures like mods, skins and hippies borrowed liberally from other cultures and eras.

For some time I’ve wanted to write something on the strange continuities and discontinuities that exist within youth culture. We tend to think of subcultures as existing within particular time periods and attaching themselves to particular types of music. For example Teddy Boys = 1950s = rock ’n’ roll. This is quite natural, of course. But this can lead to misconceptions, often perpetuated by the media. For example, the Ted style actually predated the arrival of rock ‘n’ roll in England by several years.

Some sociologists have argued that counter cultures emerge in periods of rapid economic change and reorganization. With the flourishing of youth culture in the post-war period youth became not so much an age category or a biological period of development as an index, metaphor or manifestation of social and cultural change. This relationship between generational change and social change was recognised as early as 1927 by Karl Mannheim:

'The fact of belonging to the same class, and that of belonging to the same generation or age group, have this in common, that both endow the individuals sharing in them with a common location in the social and historical process, and thereby limiting them to a specific range of potential experience, predisposing them for a certain characteristic mode of thought and experience, and a characteristic type of historically relevant action’. (‘The Subcultural Problem of Generations’)

As youth culture matured over generations the attachments (or ‘homology’, to use the academic term) between subcultures, zeitgeist, art, fashion and music (‘the predisposition to a certain characteristic mode of thought and experience’) became self-conscious and hardened, ossified. For example, punk as a subculture cohered entirely around fairly circumscribed artistic forms and refused to countenance the idea of being influenced by anything from the past (the ‘Year Zero’ rhetoric). But within subcultures there are often temporal discontinuities (e.g. elements of retro-revival) which are interesting in themselves. For example, despite this Year Zero rhetoric, punk as a subculture cohered around roughly the same kind of anti-establishment attitudes that many hippies had espoused in the ‘60s, and picked up on many of the musical strains of the earlier period. As Jon Savage reflected in 1983,

‘Punk always had a retro consciousness – deliberately ignored in the cultural Stalinism that was going on at the time – which was pervasive yet controlled. You got the Sex Pistols covering Who and Small Faces numbers and wearing the clothes from any youth style since the war cut-up with safety-pins…Vivienne and Malcolm buying up old Sixties Wembley pin-collars to mutate into Anarchy shirts.’ (Time Travel: From the Sex Pistols to Nirvana: Pop, Media and Sexuality, p 145).

A useful shorthand to describe a desire to lay waste to the bloated, complacent and conformist music industry or ‘establishment’, the Year Zero rhetoric also concealed borrowings from 1970s glam and pub rock; 1960s psych, surf, garage fuzz; and 1950s rock ’n’ roll. Roger Armstrong, manager of the famous Rock On stall in Soho Market and founder (with Ted Carroll, who was interviewed extensively for Max Décharné’s wonderful recent book on Teddy Boys) of the independent label Chiswick Records, recalled how the second-hand stall gave the kids who were in the first punk rock bands access to music they wouldn’t otherwise have heard. As well as contemporary imports that were otherwise impossible to acquire, this included the music of the ‘sixties garage scene’, leading to a history of cover versions, ‘from Flamin’ Groovies numbers through to Standells and Chocolate Watchband’ (quoted in Savage’s England’s Dreaming Tapes 2009, p. 141).

The rediscovery of some of these songs via record stalls or shops like Rock On fuelled the punk movement, just as the discovery of records by Louis Armstrong and King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band inspired the jazz revivalists of the 1950s.

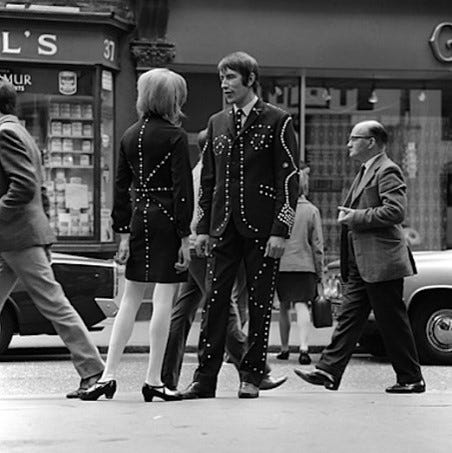

What is also often overlooked is that punk built on years of ‘50s retro-revival. In the UK this revival was spearheaded by a concert at the Royal Albert Hall by the ageing rock ’n’ roll star Bill Haley. For members of the anti-establishment Teddy Boy subculture, Haley’s concert was like an audience with the Dalai Lama. For Teds of the early ‘70s, their allegiance to this earlier era expressed deeply held class affiliations but also became a form of cultural reaction. The Teds were left behind as 1960s British popular culture veered towards Pop Art. The embrace of irony and camp clashed with the earnest fashion cues of the Teds. A similar phenomenon could be seen in the fracturing of the mod subculture - the more extravagant mods became caught up in the fashionable Carnaby Street scene (‘peacock mods) and new sounds from the UFO Club, whereas the ‘hard mods’ (wearing heavy boots, jeans with braces, short hair) stayed close to their working-class roots, rejecting psychedelic rock and prog and championing ska, rocksteady and reggae. The skinheads grew out of this faction and quickly came to constitute an identifiable subculture of their own.

In August 1972 50,000 fans attended the London Rock and Roll Show held at Wembley Stadium (featuring Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, and Bill Haley, plus UK-based support acts). Films like That’ll Be the Day (1973); Lords of Flatbush (1974); American Graffiti (1973); Grease (in the theatre 1972; on film, 1978) and TV shows like Happy Days fed the craze. Like punk, all this was rooted in a desire to recover the excitement of what Nik Cohn termed pop’s ‘first mindless explosion’.

Nostalgia for the excitement and simplicity of early rock ‘n’ roll informed the glitz and glamour of new pop acts like T-Rex, Showaddywaddy, Mud, Sweet, Slade and Suzi Quatro. Arguably the most significant exponent of this retrospective trend in Britain was David Essex. For one week in September 1973, he was at number one in the pop charts with ‘Rock On’, and in the same year he starred in That’ll Be the Day (1973) alongside Ringo Starr and Billy Fury. The film examined the impact of rock ‘n’ roll on 1950s British teenagers, with Jim MacLaine (Essex) rejecting the academic prospects of his grammar school education in favour of a life of fairgrounds, sex and music. In one revealing scene Jim, complete with quiff and tight jeans, meets his closest sixth-form friend Terry Sutcliffe (Robert Lindsay) at a college dance where Terry’s fellow students are entertained by an early 1960s ‘trad’ jazz band. The attitudinal differences are magnified by Jim’s contempt. Jim’s response to Terry’s opinion that rock ‘n’ roll is dead and ‘trad’ is the thing? ‘Bollocks’!

When Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood – who would become the two great visionaries of the punk movement – founded Let it Rock in King’s Road in Chelsea in 1971 (later to be renamed Sex), the boutique became so well known for its narrow drainpipe trousers, winkle-picker boots, and Buddy Holly records that the film director Claude Waltham asked Westwood to design the costumers for That’ll Be The Day. As Elizabeth Guffey has noted (Retro, pp. 104-5),

Graced with a jukebox brimming with 1950s, it was decorated with an odd blend of 1950s artefacts, including suburban furniture, James Dean memorabilia, film stills from 1950s classics and stacks of old movie and pin-up magazines. Ted shoppers at Westwood’s King’s Road store were increasingly dismayed to find drainpipe trousers sold next to latex gear, and drape jackets held together by safety pins. Survival and revival began to blur…

Several of the proto-punk bands of the 1970s drew heavily upon the ‘50s. The MC5’s debut studio album Back in the USA opened with Tutti Frutti and concluded with Back in the USA. As Ryan Settee has observed (over at the fabulous Perfect Sound Forever) the Flamin’ Groovies anticipated punk in ‘managing to distil all the elements of the ‘50's and early to mid '60's into an inherently less studied version than pure '50's revivalists like the Stray Cats, Reverend Horton Heat and Dave Edmunds (the latter of which went on to produce 1976's Shake Some Action)’.

Even punk’s DIY culture and visual aesthetic often owed a debt to the 1950s. Punk rock promoters looked to adopt - and subvert - fifties Modernist design. Alternatively exciting and frightening, Modernism alluded to nuclear threat and captured something of the peculiar alternation between optimism and gloom that characterized that decade.

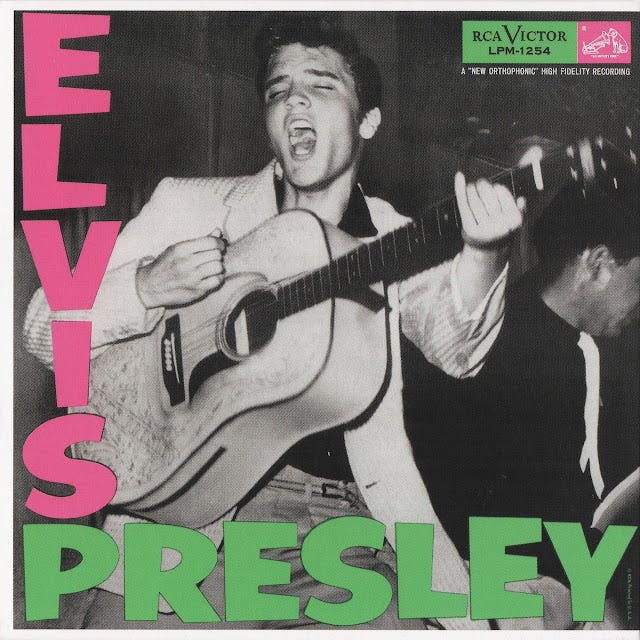

As Elizabeth Guffey has shown, the punk aesthetic sometimes took its cues from the harlequin diamonds, free-form lettering and unnaturally acidic colours of 1950s record covers. The golden age of sleeve design was quoted and subverted, with echoes of the Modernist abstractions of Saul Bass, Alvin Lustig and Alex Steinweiss.

Ray Lowry’s cover of the Clash’s London Calling in 1979 of course closely imitates the black-and-white concert photo and pink-and-green block lettering of Elvis Presley’s debut album of 1956. While Elvis’ iconic cover depicted Presley flailing away in concert on an acoustic guitar, Lowry chose an image of Paul Simonon, the Clash’s bass player, smashing his guitar against the stage.

Punk’s subversive reuse of 1950s imagery was even clearer in Lowry’s sleeve for the record’s single; imitating a pre-1958 HMV record cover, it depicted happy dancers blissfully waltzing, but Lowry’s couple skirted under an atomic cloud.

To conclude this part of the study of Subcultures and Time, it might be interesting to consider this as a story of cultural recycling and subcultural fertilisation. Dick Hebdige has suggested that subcultures are forever out of joint with mainstream dominant culture – this is precisely the point of subcultures, which are ‘reactionary’ in this sense. But punk’s proximity to the mainstream ‘50s revival that took place in the early-to-mid 1970s challenges or complicates this narrative somewhat. Whilst punk was certainly ‘reactionary’ in nature, its energy, excess and hysteria can perhaps be seen as a kind of ‘competitive subversion’, given that it was competing with other subcultural revivals, mutations or offshoots. In 1972 Pete Fowler (in Rock File Reader) recalled of the Rolling Stones Hyde Park concert of 1969:

The [Hyde Park] concert was odd. Here were the Rolling Stones, the old mod idols, being defended by the Hell’s Angels, the descendants of the old rockers, and the whole scene was laughed at by the new skinheads, who were the true descendants of the old mods…The wheel had come full circle.’ […] That July day in 1969 [when] the Stones played in Hyde Park in the afternoon; and Chuck Berry and the Who played the Albert Hall the same evening…The Skinheads announced their arrival in Hyde Park by stomping through the masses of space-out freaks, spreading their aggro and shouting their obscenities…In the evening, at the Albert Hall, their tribal enemies, the teds, their predecessors in the same estates by a generation or two, barracked the Who as they dared to play their set after Chuck Berry. They began with a truly frantic version of Summertime Blues, as the lads in front of the stage reminded themselves of old nights in the Granadas and ABCs, hurling bits of seats and bits of abuse at the ex-scooter boys on the stage.

This is the best insight into the clashes between subcultural survival and revival that I’ve ever seen. I still haven’t quite ‘unpacked’ it all. And what a day that was (must have been…). To be continued…