This is based on a conference paper that was co-written and co-presented with Prof Paul Long of Monash University, at Charles Parker Day in Salford, 22nd March 2013. Thanks to Paul for his excellent discussion of the Albermarle Report.

Generation X

I am a Millennial (I admit it!), although I’m only the cusp of being so (I was born in 1980). Really I consider myself belonging to Generation X (roughly 1965-1980). But I keep coming back to the original Generation X. The term was actually first used not by Douglas Coupland in the 1990s but by Robert Capa in the 1950s, as the title for a photojournalism assignment which investigated the lives of a group of twenty-somethings following World War II. In his introduction to the book GenXegesis: Essays on Alternative Youth (Sub)Culture John McAllister Ulrich observed,

“Capa’s use of the term “Generation X” carries with it no particular connotation beyond the fact that this particular generation remains ‘unknown’ […] the letter X is meant here to function primarily as a placeholder, a variable or blank to be filled in later.”

Generation X was therefore the original ‘Blank Generation’. As Richard Hell put it, ‘I belong to the Blank Generation and I can take it or leave it each time’. Incidentally the song itself was apparently a sort of rewrite of Bob McFadden and Rod McKuen's 1959 record ‘The Beat Generation’. This is another example of the way the creative contributions of the beats, hippies, and punks were actually closely intertwined, following on from my previous post on retro-revival.

This ‘unknown’ quality of Generation X would later translate into a desire to avoid being identified, or pinned down. In 1964 Charles Hamblett and Jane Deverson built upon the work of Capa with their paperback book, entitled Generation X, about British teenagers – many of them mods and rockers. Hamblett and Deverson conducted a large number of tape-recorded interviews, and the bulk of the book consists of verbatim testimony from the teenagers about their thoughts, hopes, fears, attitudes and lifestyles.

At the very start of the book we encounter the testimony of John Braden, an 18-year-old mechanic and Mod, who admits to being involved in the riots at Margate, saying that ‘They might've got a bit of a shock but they deserve it - they don't think about us, how we might feel…you want to hit back at all the old geezers who tell us what to do’.

After quoting from the interview, Hamblett and Deverson admit that Braden is ‘an extreme case,’ and ‘that they had sought him out because his special involvement gave him a certain journalistic interest’. Interestingly they harbour reservations about the authenticity of the interview, noting that ‘we doubt the complete honesty of his plea because we declared ourselves and thus made his reaction artificial, studied’.

This is highly relevant to any consideration of the ethics of documentary filmmaking or factual television, and, in fact, Hamblett and Deverson go on to observe that television had by this time made anyone who could string a sentence together an ‘instant pundit’. Their attitude toward television seems to be an ambivalent one, as, having said this, they then go on to propose to continue the book on the basis of ‘an impressionistic documentary’ – undoubtedly influenced by the model set by filmmakers Denis Mitchell, Philip Donnellan and John Boorman in British television, all of whom made films about young people. These films are the subject of this posts and the next couple of posts in this series.

The Youth ‘Problem’

These documentary studies had the aim of depicting a generation of youths grappling with what Douglas Coupland would eventually term an ‘accelerated culture’; dislocated by the rapid process of social and scientific acceleration. As I mentioned in the last post, some sociologists have argued that subcultures or ‘counter cultures’ emerge in periods of rapid economic change and reorganization. These subcultures and counter cultures invariably build upon cultural elements and traditions which have been supplanted or overlooked - as Georgina Boym has observed, nostalgia tends to function as a defence mechanism in a time of accelerated rhythms of life and historical upheavals.

Both in the ‘60s and in the ‘90s Generation X can therefore be conceptualised as a generation, who, in response to modernity’s crushing pace and consumerist frenzy, have willingly placed themselves on the fringes of mainstream society.

The post-war documentaries I will discuss in the post can be understood in the context of a contemporary social discourse encompassing Government departments, educationalists, sociologists, criminologists, cultural critics and the media.

In the first two decades after the Second World War, across periods of recovery, austerity and affluence, young people in Britain came into public focus as a social group around which were focused a number of anxieties. The popular press in particular played its part in a series of moral panics around what was perceived as an emerging 'youth problem'.

Concerns were centred on what appeared to be a significant growth in delinquency amongst adolescents as well as the emergence of a discernible 'teenage' culture manifest in particular uses of fashion and musical allegiances. In turn, teen culture was a manifestation of new patterns of consumption and perceptions of materialism and the impact of American culture –from comic books, to rock and roll, to what Richard Hoggart called the ‘Bogart slouch’.

In addition, National Service came to an end during this period. For two decades the majority of men around the age of 19 or 20 had gone off to serve, which must have had a significant impact on theirs and everyone else’s life when they departed and then returned to ‘civvy’ street.

Of course, there had been a substantial increase in the numbers of young people following the rise in births after the Second World War – the so-called ‘Boom’ or ‘Bulge’. In the late 1950s, there were disturbances in Nottingham and London - especially in Notting Hill and Brixton – focused upon 'race' - and involving large numbers of younger people, some of whom were blamed for the violence (the Teddy Boys, in the case of Notting Hill).

Unsurprisingly given all the media attention to such issues, there was also disquiet regarding the government's accountability. For example, a Select Committee reporting in July 1957 criticized the Ministry of Education's apparent apathy toward the Youth Service and its needs (Seventh Report from the Select Committee on Estimates: The Youth Employment Service and Youth Service Grants).

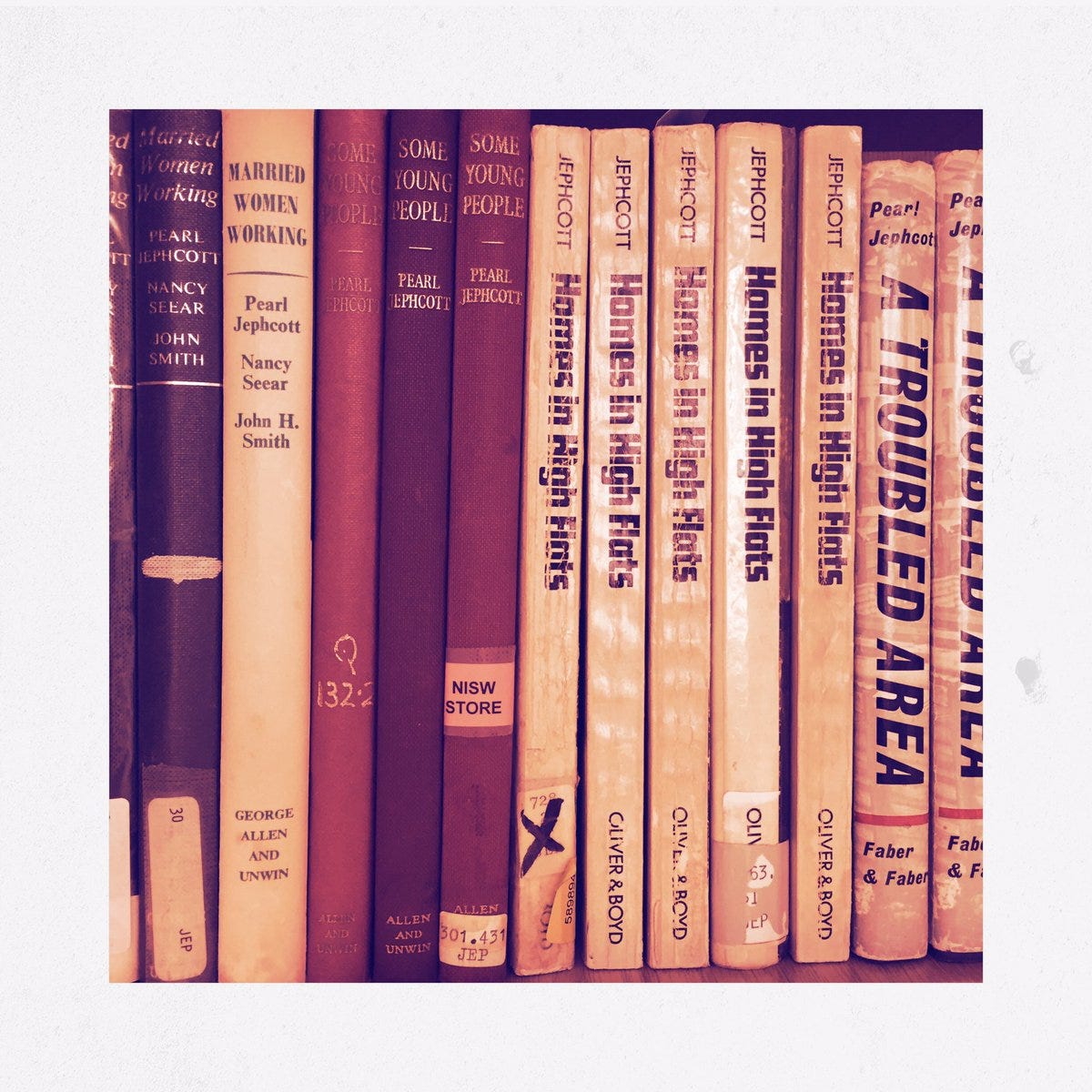

Such factors contributing to the government’s appointment of a Committee under Lord Albermarle, empowered to review the work of the Youth Service in England and Wales as a means of addressing this problem. On board were figures such as Hoggart, Leslie Paul, the founder of the Woodcraft Movement in the UK, and Pearl Jephcott, a social researcher who had written widely on the experiences of young men and women.

Jephcott had investigated youth organizations in various working-class districts of London and Nottingham, to which around a third or just over of adolescents belonged. She was particularly interested in those who had left, and the reasons they gave:

Not interested in learning knots. (Girl guide, 14)

Started going out with a boy. (Girl’s life brigade, 15)

Packed it in when I started courting. (Club boy, 16).

Too stuffy in the crypt. (Club boy, 14)

Don’t like it, don’t like religion (club girl, 14)

Too much of a family clique (club boy, 17)

Boring – you just sit there and can’t get any games because the boys bag them all. (Club girl, 15)David Kynaston, Family Britain 1951-57, p. 549

(‘Too stuffy in the crypt’ is my personal favourite). The questions asked by the Albermarle Committee crystallised a number of contemporary tropes, expressing a collective worry about young people and 'a kind of selfishness which will not yield itself to any demand outside its own immediately felt needs' (Albermarle Report 1960: 33-34). Thus, the Committee expressed a shared a concern ‘that meant from the onset all parties predominantly saw the problem as one of social control' (ibid.: 39).

It has been suggested that the Committee proceeded without conducting much original research of its own, so incorporating and reproducing many contemporary concerns. In terms of youth crime for instance, there was no substantial analysis of the changing social context of crime, of the role of the media as amplifier and generator of moral panics, nor indeed of statistical evidence actual trends and patterns. As a result, the Report highlighted of 'a new climate of crime as being being 'very much a youth problem' (1960: 17). Furthermore, this 'youth problem' was predominantly viewed as a working class phenomenon’.

While the Committee reproduced contemporary concerns, the various perspectives of its members contributed to it insights into the ways in which the experience and disposition of young people were perceived. A ‘generation gap’ was evident as the committee was struck by the language employed by many around youth work - and the extent to which ideas such as 'service', 'dedication', 'leadership' and 'character-building' were used 'as though they were a commonly accepted and valid currency' (op. cit.). The report declared,

We in no way challenge the value of the concepts behind these words, or their meaningfulness to those who use them. Nor do we think that young people are without these qualities, or that they cannot be strengthened. But we are sure that these particular words now connect little with the realities of life as most young people see them; they do not seem to "speak to their condition". . They recall the hierarchies, the less interesting moments of school speech-days and other occasions of moral exhortation. (1960: 39-40)

Ultimately, such reports, and indeed, the documentary films I will discuss, attempt to avoid depicting a youth problem as such but inevitably grapple with the very idea of a problem of youth. By this I mean a pathology that identified an amorphous group as sharing particular social and cultural traits that marked them out in essential ways from the rest of society.

Britain’s Teenagers

In 1955 the talented radio producer Denis Mitchell began a television training course at Lime Grove, and, working alongside his close colleague Norman Swallow, made his first film, which was a short ‘report’ about five teenagers in London for the pioneering current affairs series ‘Special Enquiry’, broadcast on 1st November of that year.

A few years after the original short film had been made (in 1958), Mitchell and Swallow revisited the teenagers, shot new material and created a longer film. As the camera followed them into cafes, fairgrounds and nightclubs, they spoke of their dreams and ambitions. The Radio Times described the film’s teenagers as follows:

The film starts with Mike and his friend Pat, who wear Edwardian suits, and who live and work around Pimlico. We go with them as they visit the barber and tailor, as they play football and cards, as they sit around in pin-table saloons and cafés. Next comes Lynette, who works as a photographer’s model. Lynette is a debutante, and we visit her Finishing School, her home in Scotland and the London flat she shares with her sister. We go with her to her agent’s office, and to a theatre and a party. Teenager number four is Philip, who’s a student at the London School of Economics. He lives in Teddington, and is a ken amateur actor and motorist, and takes a confident and optimistic attitude to life.

This would prove to be probably the only serious portrayal of Teddy Boys, at the height of the subculture. But Mitchell had discovered some distinct and lively characters from across the British class ‘spectrum’: Mike, the Teddy boy whom his father describes as being like ‘a trapped animal’ after being evacuated during the war in the countryside and returning to the big city; Pat, Mike’s close friend and fellow Teddy boy who became a sixties mod: a restless spirit who rode the wave of modern youth culture, living for the moment in the belief that nuclear annihilation was just around the corner…Lynette, the debutante attending finishing school who used to dream that in a previous life she was Catherine Howard; Phillip, a scientifically-minded and utterly conventional student at the LSE; and Diane, a firm believer in marriage and family life with modest aspirations, who is still at school, but who nevertheless rejects the Bible and attends parties and dances the ‘bop’ at Humphrey Lyttleton’s jazz club.

Roughly ten years after the original Special Enquiry film, Mitchell and Swallow re-visited the young Londoners again to see how their lives had turned out for a new documentary, which was Mitchell’s last doc for the BBC, entitled (of course) Ten Years After. Around the time he made this film Mitchell moved to Granada, where he mentored the young Michael Apted. Surely it was no coincidence that the film was broadcast the same year as the first installment of the longitudinal Granada documentary series ‘7 Up’, which documented the lives of a group of children who the team then revisited at seven year intervals.

What is remarkable about Ten Years After is actually how closely and consistently the twenty-somethings adhere to fundamental aspects of their previous identities as teenagers. Mike and Pat - now mods rather than teds! - are still pals as in the previous film, and now work together as window cleaners. Scenes of them cycling down a London street, with Pat holding their unwieldy long ladder, almost knocking down several pedestrians, could have been straight out of a British New Wave film of the period!

Both young men are acutely conscious of class divisions – but whereas Mike feels unconstrained in terms of his personal development – saying that whilst he hasn’t moved up the social ladder, ‘everything is wide open’ – Pat is frustrated with the assumptions and stereotypes people have about East End boys (he describes himself as ‘a 150% cockney boy’), and believes that he will not be able to find other work due to the fact that he cannot speak ‘good English’. However, whilst Mike is frustrated that they do not make enough money, but Pat opines that they have ‘a rich life compared to previous generations’.

Mitchell recalls via some narration that he had asked them in the previous film what they see themselves doing in 10 years time, and had got the overall impression that they were scared that convention or conformity would strangle them. Mitchell notes that there does not seem to be much evidence of this, as the boys are lively and outspoken, and enjoy going to nightclubs. Mike and Pat had played a very enjoyable part in the previous film, and in this sequel Mitchell makes full use of their amusing repartee. In this film, Mitchell unites Pat and Mike with each of the other teenagers in separate scenes, so that the differences in personality and outlook - and class distinctions - are best exposed. Of the group they had only previously met Diane. In this film Pat asks Lynette, a deb-model in the previous film now married with a child, what her parents would think of him, and the resulting chat hinges on class differences. Afterwards Pat and Mike talk to each other about Lynette, with Pat saying ‘She’s like pound note…she is pound note!’ and ‘that’s marriage for you!’ so on. In this way they act as alternative narrators – almost like a Greek chorus. Pat’s encounter with Diane, who he had met and argued with in the previous film, is in some ways like a replay of their previous encounter, with Diane attacking Pat for generalising from what appears to be his rather sour and disillusioned experience of relationships. At times during the film it seems clear that Mike is more carefree than Pat and that he finds it easier to extricate himself from the limitations and determinations of the British class-system.

Despite the fact that he and Swallow stayed in contact with the group of young people, Mitchell refrained from capturing them again on film, as that was bound up with his BBC career. However, when On the Threshold was repeated in 1977 (for Festival ’77, a series of programmes selected from the BBC television archives to commemorate the Jubilee Year) there was a partial reunion hosted by Rene Cutforth after the transmission, with three of the ‘teenagers’ discussing how their lives had progressed in the meantime. Pat, Philip and Diane all recognised their younger selves without much embarrassment or sense of separation. In 1977 Pat was still a window cleaner and, whilst professing to enjoy the physical labour of the work, seems resigned to a nagging sense of inferiority in interactions with others perceived as higher up the social ladder (pun intended). In the discussion Pat says that he is ‘trapped as the happy bachelor’ because he has no financial security to attract a long-term partner.

As a coda to this story, I happen to know that, circa 2015, a filmmaker attempted to make another film for television revisiting and reuniting the ‘teenagers’ fifty years later. He tracked down some of the people from the films (including Pat and Lynette), undertook some interviews, and created a great teaser trailer, but failed to get it commissioned. I’m still sad about this, especially as, even from what little I have seen of the interviews, they contain personal and emotional stories from some of the groups which put the previous films in perspective. This would have added layers to the social history, and would have also added layers of pathos to our understanding of the callow youth caught on film.